A model of multisecond timing behaviour under peak-interval procedures

Read:: The first part, not exactly relevant Print:: ❌ Zotero Link:: NA PDF:: NA Files:: A model of multisecond timing behaviour under peak-interval procedures - 11.07.22.md; Hasegawa_Sakata_2015_A model of multisecond timing behaviour under peak-interval procedures.pdf Reading Note:: Takayuki Hasegawa, Shogo Sakata 2015 Web Rip:: A model of multisecond timing behaviour under peak-interval procedures - 11.07.22

Abstract

In this study, the authors developed a fundamental theory of interval timing behaviour, inspired by the learning-to-time (LeT) model and the scalar expectancy theory (SET) model, and based on quantitative analyses of such timing behaviour. Our experiments used the peak-interval procedure with rats. The proposed model of timing behaviour comprises clocks, a regulator, a mixer, a response, and memory. Using our model, we calculated the basic clock speeds indicated by the subjects’ behaviour under such peak procedures. In this model, the scalar property can be defined as a kind of transposition, which can then be measured quantitatively. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) values indicated that the current model fit the data slightly better than did the SET model. Our model may therefore provide a useful addition to SET for the analysis of timing behaviour.

Quick Reference

Top Comments

Topics

Tasks

—

Extracted Annotations and Comments

Interval timing is based on time perception. The mechanisms of circadian timing and millisecond timing have been clarified, to some extent.

Interval timing, however, differs from circadian timing and millisecond timing in its precision.

Interval timing is less precise than either of the other two types of timing: it is accurate only to within a wide seconds-to-minutes-to-hours range, while circadian timing is precise to within a narrow range of around twenty-four hours, and millisecond timing is of a mixed precision that lies within the subsecond range (Buhusi and Meck 2005). Given this difference in precision, it is likely that the mechanism underlying interval timing differs from those underlying these other two forms of timing.

In the current study, fixed interval (FI) schedules of reinforcement were used to study interval timing. With FI schedules, only the first response that occurs after a fixed duration is reinforced.

To better study the full course of responding over time, Roberts (1981) invented the peak-interval (PI) procedure. The PI procedure includes both FI trials and probe trials. In probe trials no reinforcement is provided, and the length of the trial greatly exceeds the length of the intervals used during the FI trials. Interval timing is often investigated through use of the PI procedure (See Fig. 9 for actual data from our experiment, shown as dots; also see Fig. 2 in Church (1984); Zentall (2006)).Footnote 1

SET and LeT

Investigations of vertebrates’ sensitivity to time have culminated in many theories. Among them, the scalar expectancy theory (SET) model and the learning-to-time (LeT) model are mathematically interesting.Footnote 2

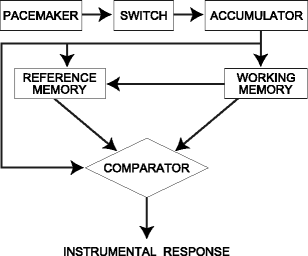

Gibbon (1977) and his colleagues developed the SET model of timing (Gibbon 1977; Gibbon et al. 1984). SET is very successful at describing subjective time across many interval lengths. In short, SET provides a cognitive and stochastic account of information processing to explain temporal behaviour in animals. The components of SET are a pacemaker, a switch, an accumulator, memories, and a comparator, and the model proposes that together these components produce instrumental responses (Fig. 1. See also Fig. 1 in Allman et al. (2014) and its detailed neurological review). The explicit solution of a PI procedure is

(1)

where R(t) is the operant response function at time t, t 0 is the t-coordinate of the vertex of the graph of R(t), b is the standard deviation, and a and R 0 are parameters. This is a modified version of the density function for the normal distribution.

Fig. 1

Structure of the scalar expectancy theory (SET) model, updated by Fig. 1 in Allman et al. (2014). A pacemaker generates pulses. Pulses are first stored in an accumulator and then stored in the working memory. After reinforcement, the contents of the working memory are transferred to the reference memory. In later trials, previous delay lengths stored in the reference memory are compared with the number in the accumulator, and the ratio of the two numbers determines the subsequent behaviour

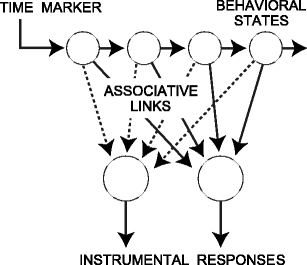

Machado (1997) developed the LeT model of timing, retaining the basic elements of the behavioural theory-of-timing (BeT) model, which was developed by Killeen and Fetterman (1988); Machado (1997); Machado and Guilhardi (2000); Killeen and Taylor (2000).Footnote 3 In short, the LeT model is a behavioural and deterministic account of learning formulated to explain temporal behaviour in animals. Its components, which include behavioural states and associative links, produce instrumental responses (Fig. 2). The LeT model therefore describes a dynamical system that individuals use to produce temporal behaviour.

Fig. 2

Structure of the learning-to-time (LeT) model. A time marker initiates the activation of behavioural states. These serial states are multiplied by each associative link. The summation of these products determines behaviour